Forbidden Fruits | travel writing

Barcelona, 2 October 2017

After our observations in the morning, we only stayed home for a brief moment. We headed to Gracia, to look after the kids so that Manda could go and vote. Aurélie persuaded me to hurry up and skip the shower. “Now that her family had to cancel, I want to show to her that you can rely on anti-family.”

Looking after Alba and Bernadita did not require much work, because besides being the most well-behaved children in the world, they had received extraordinary permission to spend the whole day playing with their iPads. Manda was nervous. She isn’t usually an activist, she is the sorted, sober person in the family, bringing up her daughters and having an academic career. Her parents have always been politically active, supporting the socialists. She mentioned how her mum smuggled French books – philosophy for herself and “Barba Papa” for the children – across the border into Franco’s Spain. Recently, her father had become very involved in the independence campaign. Manda insisted that we didn’t talk to the kids about the police violence we had just seen. It made me realize again in what a narrative environment I grew up. I thought one should sit down and tell the entire history from the Spanish Civil War onwards to the girls, so that they would understand what was going on. I then realized that I didn’t know anything about that history myself – reading Peter Weiss, as Sabine had urged me to, had left me with an overwhelming feeling of commitment and inadequacy to the task, but without the relevant dates. In between emails, Twitter, and commenting on Rahel’s recent paper on Resentment and Regression – which seemed uncannily timely –, I tried to read up on Wikipedia. By now, I again only remember that the crown was always on the wrong side of history, that the Spanish did not have World War I but infinite numbers of military coups, that something equivalent to the Weimar Republic in Germany only lasted a good two years in Spain, and that the Civil War started in 1936. It is striking to see the maps which show a purple enclave in the North East of Spain in that context. Catalonia was the stronghold of anti-fascism, the centre of the decentralized anarchist organization, always on the side of the Republic. Back then, they were apart because they stood for a different whole, not just for separation.

I kept emailing back and forth with Ann, always a source of links and facts and careful judgment. As so often, I found the twitter-embedding journalism which the Guardian and the BBC have adopted more confusing than Twitter itself. I finally trumped Ann’s analytic energy by forwarding the Jacobin analysis. Interestingly, after all their talk of seizing the state in the last issue, they still aligned with the separatist forces – if only to weaken the reactionary state in power.

Aurélie reheated chicken stew for lunch, for dinner we made some vegetables and rice, which I overcooked as always. The girls liked it and said unlike the food we had made for them when they visited us at Home, it wasn’t weird. With the help of YouTube, they taught us a song about animal sounds. The main character was a little chick, making “piep” in the refrain. After all the other animals, a tractor shows up and runs the chick over. But then there is another version in which the chick does weight training along with saying “piep” throughout the song and then punches the tractor flat in the last stanza.

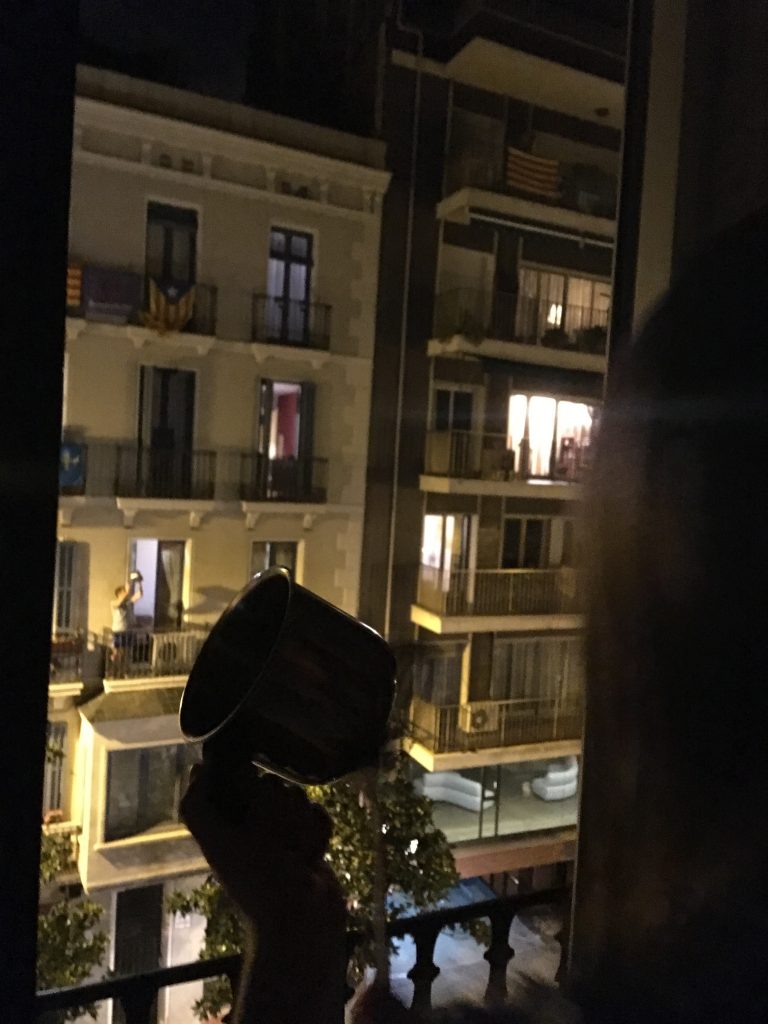

Manda had been asked to stay at the voting station by the organizers. She met some parents from the kids’ school and seemed quite happy about a day spent not with work. Everything had remained quiet. Like the rest of her family at different ballot stations, Manda was able to cast her vote. She came home at 10pm. A small saucepan and a ladle were already positioned on her dresser. We took turns leaning out of the bedroom window, overlooking the wide Gran Gracia avenue and joining in with the Cassolada concerto. The rattling noise, amplified and reciprocated, was great fun. But it was also obvious that less than half the households took part in the exercise.

Aurélie and me took the Metro home. On the walk from Barceloneta station, when we crossed the market square, I noticed a lone man diving in the rubbish containers. I suddenly felt very demoralized. There is this clarity, immediacy, and excitement to violence – especially for its critics. As long as it happens in the right place, it is as absorbing as beauty. It lends itself so well to campaigning. But what image on twitter would have sparked international outcries, requests for an immediate end to all conditions that humiliate people by social neglect, rather than state violence?