Is the family a grave? | travel writing

Verona, 29 March 2019

I’m on the train from Verona back to Rovereto. I am exhausted and feel tired and saddened. It might just be that post-limelight-low and -loneliness. There was a tall, young, incredibly beautiful person in the audience of our podium and at the community event afterwards. Glamorously androgynous, with shaven head and velvet brown eyes, the kind local wore almost the same black-and-white-striped shirt as me. They thanked me and called the input “bellissima”. Earning disbelief that I might be able to afford a taxi, I had been shown to the bus.

The city bus 13 made its way through rickety side streets, approaching the station. I hadn’t expected at all that it might go past the municipal hall. I jolted when I saw it out of the window, the gigantic banners of the World Congress of Families hanging between the sand-stone columns. I don’t know what I had been thinking. I must have secretly imagined that event – the very occasion of my coming to Verona and preparing a little talk for a panel on feminist solidarity – in some sort of desert. Several people had already explained the significance of the choice of location to me. Verona, the first host-city of the WCF in Western Europe. Verona, the strong-hold of the Lega Nord. Verona, where Mussolini founded his separatist North-Italian fascist republic after the defeat in 1943. Within the reach of the University, Lorenzo had walked me past the shop-fronts of two Neo-nazi associations. Besides Forza Nuova, there also is Casa Pound, named in honour of the poet Ezra Pound and located directly opposite a women migrants’ centre. And yet, before my inner eye, I seem to have situated the WCF venue and all its self-proclaimed “leaders” outside the city-walls, in some imaginary waste-land, if not on Mars.

But there it was, and suddenly I felt bitter about the contrast of this bombastic facade, its over-sized glass doors in copper frames, its marble steps, to the crammed little LGBTI-refugee meeting space and the backyard-townhall where our events had just finished.

I was – am – still frozen under the spell of a little video-documentary shown at the queer refugee place. It was produced in Uganda and opens with a cartoon-reconstruction of the main protagonist barely escaping after his house was set on fire. After that, there was footage of anti-gay demonstrations and random street-interviews. The defaming accusations mostly sounded familiar, but the one response that really stuck with me was “I don’t know what they are, but they should all be killed.”

There is this way that eyes can harden; it goes with the unnatural certainty in the voice which declares who doesn’t deserve to live. I recognize this so well that I find it almost impossible to fight back a universal depression, the feeling that this is just the way it is, that we will always trigger that impulse to murder. The feeling that had made me take off my AIDS-solidarity-ribbon as soon as I was alone on the street, the feeling that makes me compulsively friendly to the firefighters in our Brandenburgian village lest someone should take kerosin to our house. I know that this is wrong, I know that there is a history and a social structure behind those impulses everywhere. Before colonization in 1894, multiple tribes on the Uganda-territory took for granted bi- and homosexuality as well as a third gender. The Catholic church only recently got fixated on “gender-ideology” in an attempt to divert attention on their abuse scandal. Brandenburgian neo-nazis in our region are known to threaten immigrants much more than queers.

After our podium, Adriana and me had stopped in a tiny little street bar to down two grappas. Adriana told me about that time in the UK when she’d given a lecture on war photography, poetically entitled “The apple of the eye and the eye of the beholder” and afterwards been attacked for not having used trigger warnings. “But what are trigger warnings?” Adriana had asked in full honesty. The discussion had turned intense and interesting, with another Balkan expat insisting that the very idea of those warnings seemed to ignore the fact that for some, the violence of these images were the fabric of everyday life. It was also Adriana, fearless of triggers, who asked the main protagonist of the Ugandan film, Najib Kabuye, who was present at the screening, about choosing exile. He said that he worried about who’d be left to fight. But after he spent two months in hospital, recovering from the beating which the eight men only stopped because they considered him dead, he decided it was time for leaving. I felt embarrassed about conflating the fears arising within my sheltered life with his journey. And yet I couldn’t help to see myself inside that burning house inside my head.

Lorenzo, on the other hand, was a bit suspicious about the success of the mobilization for the counter-demo tomorrow. “I hate to be a killjoy,” he said, “but I feel funny about it. Maybe it works only as long as we don’t talk too much about migration”.

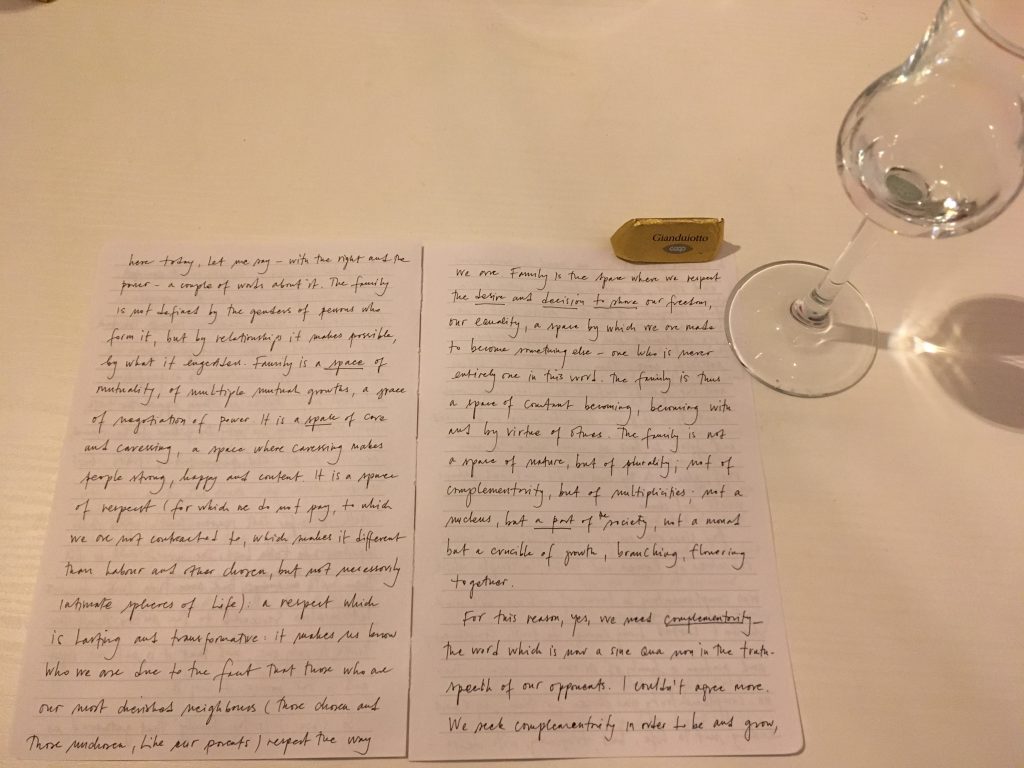

I had enjoyed thinking about my little speech, and had loved Adriana’s, which she’d allowed me to read the night before. She made a very funny and elegant reference to Romeo and Juliet – advertised as a monument to heterosexuality on the WCF’s website – and emphasized how hatred projected onto kinship-structures, as in racism and ethnic hostility, had kept them from ever forming a family.

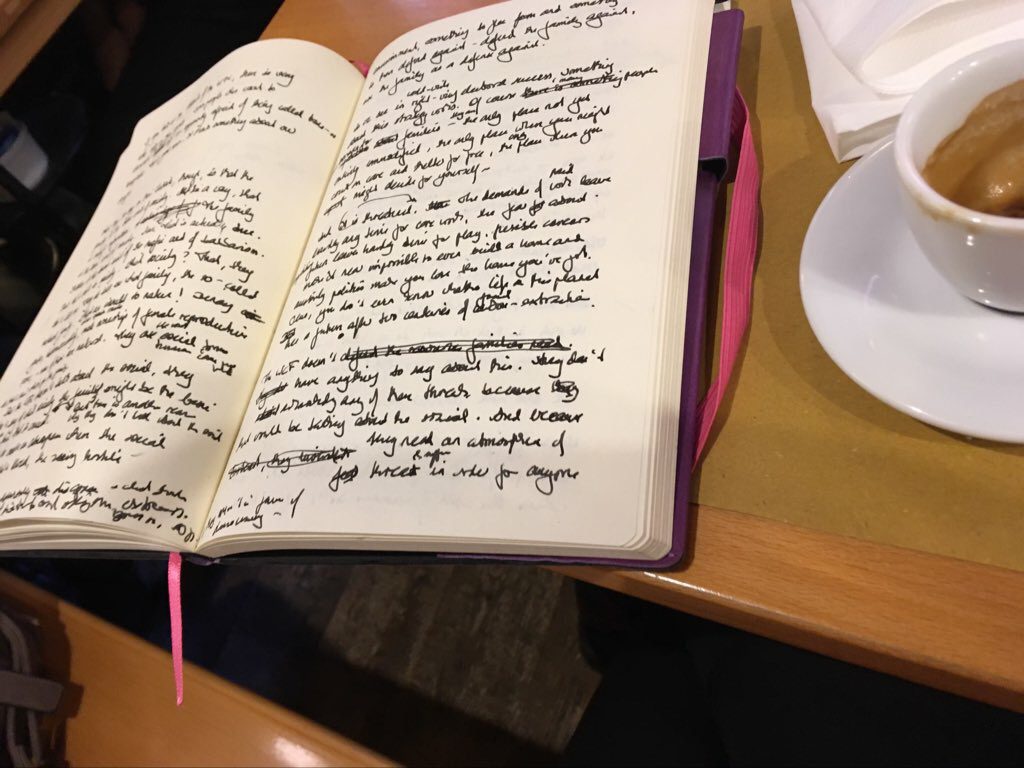

But right now, I feel irritated about everything any of us said at that event, I feel irritated even by the beautiful image of non-violent, open family-ties that Adriana crafted. I find it unbearable how we have already turned research on Anti-genderism into a trade, gathering elaborate counter-conspiration-theories and fighting amongst ourselves about who is an outright fascist and who should merely be called ultra-conservative, then ending on a few bullet-points of strategic advise for the resistance. And most of all, I irritate myself. This whole socialist-feminist pitch about how only “they” need to obsess about the family while “we” have an analysis and a vision for the whole of society. It isn’t even true, and besides, it’s a vain attempt to embrace everyone. A coward avoidance of occupying our spot of negativity which has no dialectical emergency exit.

Yes. We are the death of your family. We know it, because we can see it, reflected in that dead spot in your eye ready to kill us.