Swimming towards Mussolini | travel writing

Lake Garda, 14 September 2018

I swam to Mussolini’s palace every day while on holiday. The Villa Feltrinelli served as his base after Mussolini was toppled as Italian leader, yet hang on to a bit of North-Italian territory known as the Republic of Salò. The lake-side residence is visible from afar, even through the mist, painted in shrill yellow and pink. Built at the end of the 19th century by a paper factory owner, the place is a failed mix of exaggerated fortification and candy-decor.

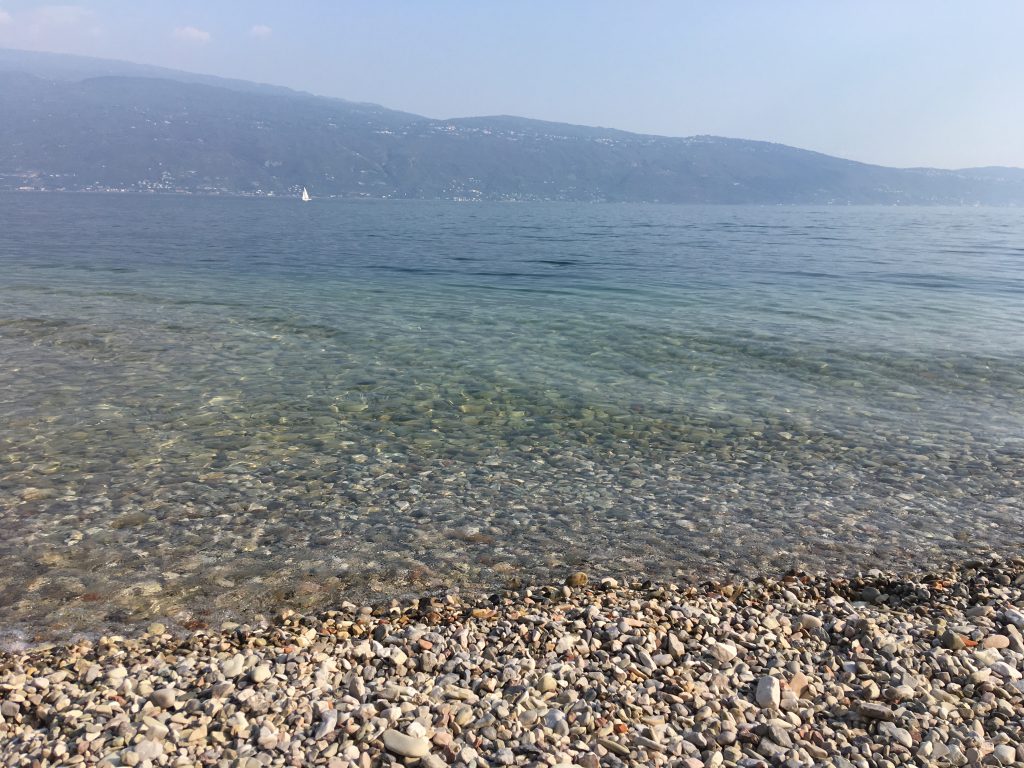

I had promised to Aurélie that I wouldn’t swim too far off the bank of the lake. In long and slow strokes, I moved past houses with their little jetties, a building site, the stony tourist-beach, and a surfing school towards the dark, green park surrounding the palace.

I could hardly resist the temptation to veer towards the centre of the lake. On either side of the water, the mountains rose up, forming a portal around the long, open stretch of horizon in between. This fostered the illusion of traversing the open sea, as if behind the point where sky and water touched lay infinity, and not Riva del Garda.

It was late in summer, yet the water felt still warm and looked very clear, polished by the stones it was set in. No plants, not even lose leaves. I only came past a lemon floating calmly on the surface, emitting an almost unreal perfume.

I tore my eyes from the horizon and looked up to the mountains. Aurélie never understands how I can be less afraid of water than of mountains. Trekking along those narrow paths strikes me as very dangerous. Maybe the difference between us is that I start from the assumption that one is always already falling. How then not to prefer the softly carrying element to a steep, hard surface.

I revel in the joy of swimming: stretching ones limbs and never meeting any resistance. After the first, fresh prickle of the water on the skin, no further reminder of one’s contours. Where I end might be at the foot of the alps, or just as well I might have vanished, absorbed by the lake, already. “Italians all over the world, beyond the mountains, beyond the seas, listen,” demanded Mussolini when about to invade Ethopia. His rhetoric didn’t just address the people, but conjured their changed contours: “Twenty million Italians are at this moment gathered in the squares of Italy. It is the greatest demonstration that human history records. Twenty millions, one heart alone, one will alone, one decision. This manifestation signifies that the tie between Italy and Fascism is perfect, absolute, unalterable. Only brains softened by puerile illusions, by sheer ignorance, can think differently, because they do not know what exactly is the Fascist Italy of 1935.”

I constantly need to remind myself to aim for Mussolini’s castle. While not fearing the water, I don’t like to come too close to the territory of boats and ferries. Nevertheless, a yacht passed by quite close to me. It was definitely them who had come too near to the shore, not me off it. The boat-owner in his white polo-shirt gestured towards me, disdainfully tapping his chin from below, apparently suggesting that I lift my head more in order not to be hit by his bow wave. I felt insulted on various levels, but also weirdly satisfied by my secret knowledge: I had long merged with the water and the only one drownable was him.

Behind the palace, like a dark drapery, the sky had turned steel-gray. A thunder grumbled behind the mountain ridge. When Mussolini declared war on France and England in 1940, he presented it in terms of thunder and lightening: “An hour appointed by destiny has struck in the heavens of our fatherland. (Very lively cheers).” While automatically moving arms and legs, I tried to work out in my head what exactly was dangerous about swimming in a thunderstorm. Would I be electrocuted should the lightening strike the lake? I was earthed via the water, so the shock would obviously be wired through me. But then, didn’t the charge get diluted by the enormous amounts of water? Probably the only danger was a head too far above the surface, which might attract the lightning directly. In this regard, the boats and the copper linings on Mussolini’s roof should prove protective. As imposing as the palace looked, Mussolini was tucked there as a mere puppet administrator for the Germans from 1943 onwards. An SS-unit had freed him from Italian prison at a time when the Germans themselves had already lost the war, only not admitted it.

I swam back in more haste, not entirely trusting my reasoning. The lake was cloaked in quietude. I blinked into the sun through yellow haze. The surface of the water stretched in front of me, an immense velvet bed-cloth, smoothed out by an invisible giant’s hand. A flock of ducks had evacuated the water and settled on the beach. Did the ducks know something I didn’t? They had also sat there the previous days, though, and I had thought that was to get out of the way of the swans. But there were no swans today. Did the swans know something I didn’t? Where I had before inhaled the slightly moldy citrus-scent, I now smelled sulfur. They cut metal on the building site. Did the grandparents of these builders fight in the Ethopian resistance? Or as partisans in the mountains behind them? Or did they not?

I forced myself to calm down again by focusing on the horizon at the opposite end. It was lighter there, and all the landscape ran evenly towards the same point, the foothills lowering in parallel alongside the bank of the lake. I still considered it possible that I might die in that water, but the beauty, far from urging me to preserve my senses, took the edge of that possibility. Why not? Never again to carry myself, never again to hit rough ground. Why not just as well?

Finally, the drowning-option simply faded in the background, rearranging itself with ridge and shore at the horizon, as I came closer to the pontoon I had set out from – a pontoon in considerable distance, or so it seemed to me, from Mussolini’s Villa.