Anti-Sightseeing | manifesto

Home, 1 April 2009

Travel-writing might be 19th-century, but traveling itself is at best 20th-century. My bet would be that it will soon be over. People already mostly travel because they have to, or feel they have to. It is for work – because you have a board meeting overseas or because you want to make it to Europe to find a living –, and more often it is for war. And soon it will be for draught and flooding. Not having to migrate, having a place intact enough to be able to stay there and to host others, that will become the true luxury, if it isn’t already.

I anyway never liked going on holiday. We only started going later in my childhood, and only for ten days in the autumn school vacation. It was very stressful for my parents to arrange everything so that they could leave, with my grandmother doing the shop and the apprentices looking after the farm. I never understood the point of it. Why leave your own pony behind and look at other peoples’ cows on treks through Bavaria? Why get car-sick driving through the mountains when at home you could walk to the lake? Why look at castles stuffed with old furniture, when the rest of the year we lived on the creed that nothing matters as much as the work we do, that everything is meaningful, and necessary, because the animals die without feeding and everything depends on preparing the next harvest well?

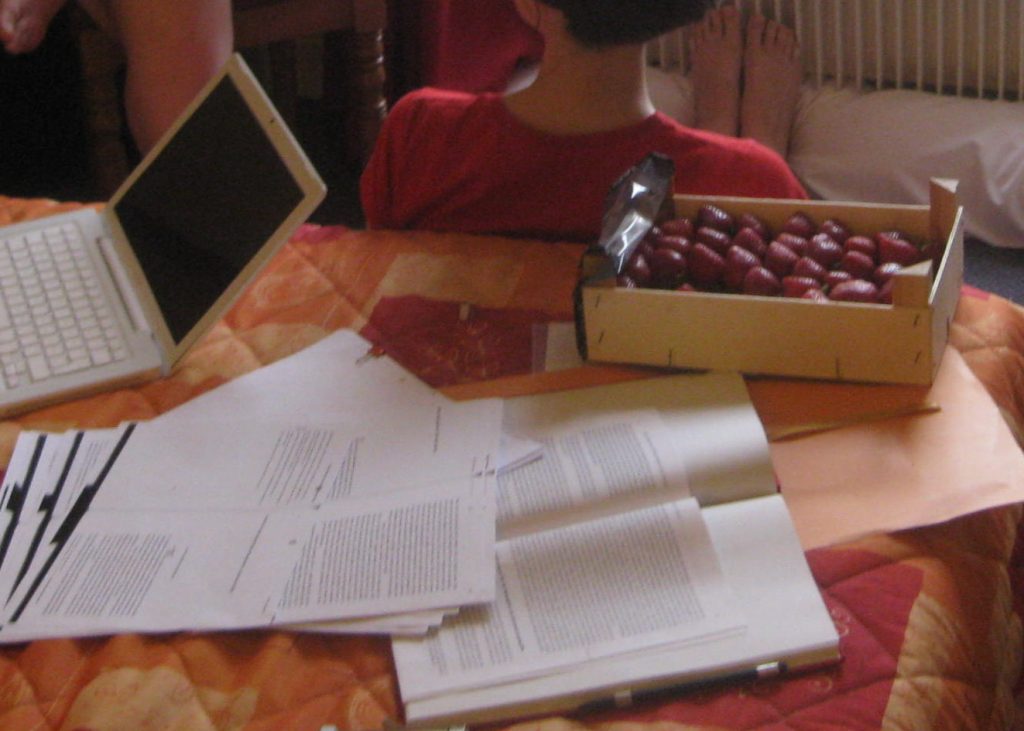

I have kept a reluctance, bordering on a tick, to visit any of the must-sees. I think I was in Paris three times before going to the Eiffel Tower, and that was only because my boss promised me champagne lunch on top. I don’t understand what I am to see there. What difference does it make that I, too, have stared at that indifferent steel construction? I was so much more fascinated by this little, far too expensive Japanese fruit shop on a busy road in the boring 13th arrondissemont, with fruit of almost artificial colours, contrasting with the gray facade and the faded shop-sign. All arranged to unlikely perfection, as though the tatty shelf was already the top of a cake. If only I had had room in my luggage for the A5 sized wooden crate that I bought filled with strawberries, all stuck with their tip up, one next to each other in diagonal lines, a perfect landscape of hard red rear sides of perfumed berries. That would have made a souvenir.

Does that mean I am stuck within the horizon of a strawberry farmer’s daughter? Is anti-sightseeing simply a lack of cultivation? Even today, I feel I’m lacking references, and equally for so-called high and low culture. We didn’t go to the Pinakothek in Munich, but I don’t know the names of Popstars from the early nineties, either. What I learned at heart as a teenager were the pedigrees of champion stallions.

I was never taught regard for monuments, and yet I grew up in an environment extremely fond of learning. My mother was an authority for knowing things. My father made the apprentices solve difficult math questions about the percentage of weight of grain added by its surplus humidity, and he insisted that even the supposedly less complex tasks required intelligence. “There is no manual work that isn’t also mental work”, he told me, slightly reproachfully but also proud to demonstrate a universal law, and then he shifted the peak of dung on my wheel-barrow from the back to the front, so that more weight rested over the wheel and less on my wrists.

Maybe this is why I focus on the smallest things as if expecting miracles from them. But more likely it is because when away from home, the most mundane things seemed the strangest. Even if lacking some cultural background knowledge – I understood buildings, and I had an idea what art was for. What I failed to grasp was the normal. Or rather: nothing seemed normal to me, everything seemed to function differently. What was it all those people in unpractical clothes were so serious about if they didn’t have farms? Which laws of leverage was I missing out on?

My first trip to Hamburg, when I was sixteen and visited my favourite cousin, was full of more detailed astonishment. He showed me the fish market in the register of sightseeing, but there was nothing extra-ordinary about that. It simply combined the job I’d do on our market-stall with the rhetorics of the horse-show auctioneer. But the things on the way: What is a fitness studio? Why do people go there? Don’t they get all the muscles they need for their work from doing that work? Are they training, like stallions, for a show? But they aren’t for sale, or are they? How on earth can the material for egg cartons hold a liquid and why would you buy a coffee on the street?

I’m not sure that traveling and observing are the best mode to fully discover those things (hence: social philosophy…). Anthropological voyeurism isn’t that much more enlightening than sightseeing. But it preserves a state of wonder which saves part of my first nature from being overridden by the jet-setting academic callousness of my second.

And anti-sightseeing keeps me occupied while, for the time being, I still have to travel. It gives me a better excuse to avoid actual sightseeing.

Sightseeing is definitely the most impoverished mode of interacting with the world. It’s careless by-passing. A lazy consumption of things one might as well look at on Google street-view now. Mere registration, by intention, and more often than not unintended devastation.

After four days in Athens writing and reading in Exarchia coffee shops, I mustered the resolve to see the bloody Acropolis. Don’t get me wrong – I am in awe with everything associated with the Acropolis. But what’s it got to do with walking along some crowded pavement, sweating like a pig, being harassed by a never-ending line-up of restaurant-owners, soda, ice-cream- and fake-handbag-vendors to then join the even weirder crowd of tourists? On the way up the hill – one of the few green spots of that city – watchmen make sure that you don’t tread aside the dusty paths. How bizarre that a once sacred location, which has been around for more than two thausand years, attracts thousands of visitors every single day but still you need people in little cement-blocks which at first sight look like mobile loos to ensure order. What’s the point of all those tourists on pilgrimage if you can’t even trust them not to trash the place?

When atop, I eavesdropped on a German couple who read out their Baedeker aloud, but I couldn’t focus on the information conveyed. The pragmatics of every sentence were screaming: “I read this, therefore I belong to a superior species”. Maybe the place should be trashed, after all.

When I work, I get desperate for having time. But holiday seems like a bad deal: time you get, but you’ve lost your place. Obviously, you go places, and they can be excruciatingly beautiful or interesting. I have very hungry eyes, I love seeing new things – a good deal of anti-sightseeing is about that, about wanting to see properly new things and not the familiar, only outside the postcard-frame.

But seeing is the most sterile sense. I feel captive and nervous visiting places without any prospect of delving in, of becoming a part, of co-creating. When I had moved to Manhattan for a semester I told a friend that yes, I had a great time, but there was nothing one could do. Obviously I did a million things, I went to places (ranging, withing the first week, from a Heinz-Werner-Henze to a “Isle of Klezbos” concert) and I got up early, propelled by jetlag and curiousity, just to walk around and see, see, see. But nothing I saw was there for me to interact with, to sustain and transform. I was not part of the reproduction of this place. I enjoyed it, but it didn’t need me.

Sightseeing is the epitome of that kind of unfreedom. You stare at what is set in front of you. The difference between your door and prison bars isn’t just that the former opens. It is that you can repair or change it.

Repairing I do a lot these days, now that Home isn’t a family-farm but an alternative-kinship-commune. It’s in the country, again, but what makes it a real place, not a sight, might likewise apply to urban neighbourhoods, socialist factories or GitHub. It’s a metabolism, a cycle, it is alive, it shelters you but you are also its input, a necessary one. Though not indispensable. Thus, when you are away, you miss out on something. It isn’t a dead place, something that will be the same upon return, and therefore bores you if you stay. It’s a place unfixed and thus alive. A place that makes you not want to travel.

The freedom to transform a place doesn’t entail that one controls the results. Often, we don’t know what we are doing, and not only because we aren’t very expert tradesmen. Our neighbour Sandy says: “why should I go abroad when you have people from everywhere next door in your garden?” We didn’t know we could have that effect.

Sightseeing transforms places, too. But often, it transforms them into something less alive.

And can you guess the deadest place in the world? Airports. I hate airports. Sightseeing is visiting places which don’t yet look like airports until they do. The same brands, the same coffee-shops, free WiFi if you part with all your data, and every rucksack not a mobile household but a potential bomb.

If airports are the future, anti-sightseeing is a tiny attempt at resistance.