The Souls of All Departed | travel writing

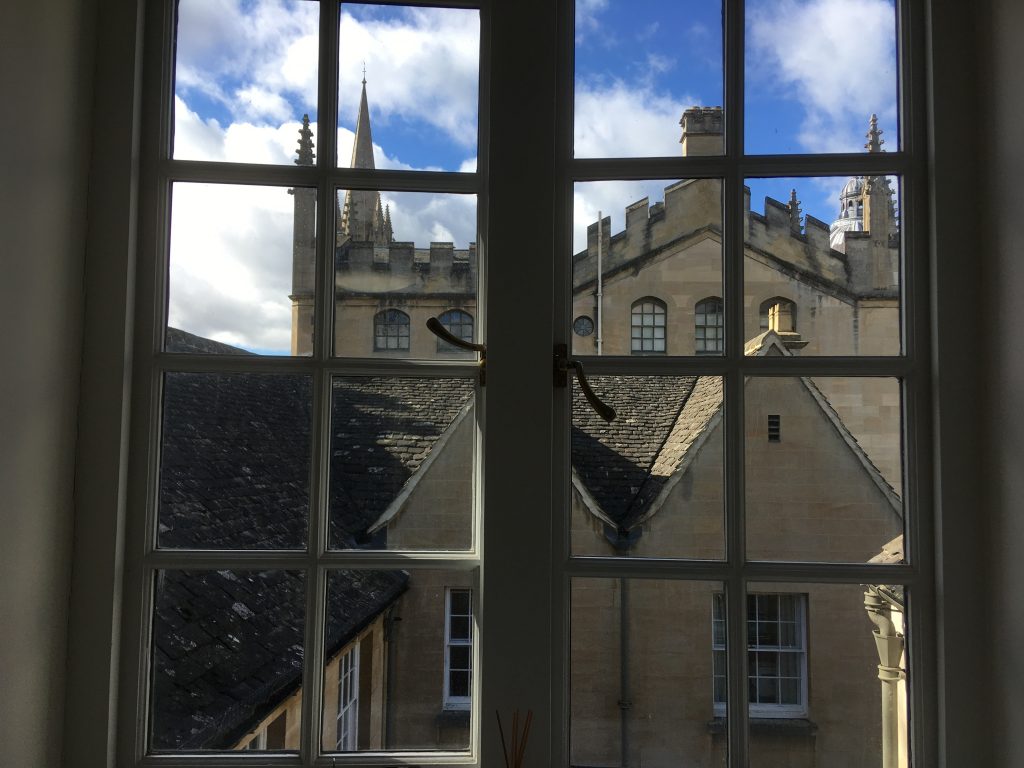

Oxford, 9 March 2018

I decided yesterday that college life was very much like commune life, except that in college, you have staff, but you cannot chose your house-mates. (And I will admit that they got significantly further with their library than we ever will.) All Souls doesn’t have any students, it is exclusively a scholars’ community, and thus also the college still most reminiscent of monastic convents.

Many small things are familiar from our own version of collectivity. You meet random people in mazes of hallways. There is an abundance of candles (though on silver candle-sticks rather than empty wine-bottles). There are enough rooms to switch to another one after dinner for cheese and port wine. And there are odd convivial rituals. For example, all the shared things (cheese, bread, port, Madeira, red wine) are passed round clockwise, except for snuff, which is passed around anti-clockwise. If there is a build-up, the youngest fellow present has to lean across the table with a wooden cane and push the bottles onwards. Earlier, after my talk, I had also had my share of that ruthlessness typical for discussions in contexts where belonging creates so much safety that you don’t need to protect each other from your true opinions.

My host and two other young female philosophers had come to dinner. Though now, for second dessert, the rule was to sit next to different people than before. You are visiting a group, not an individual. Surprisingly, my water glass – not part of any of the official commotion – had decided several times to slide left and right in front of my plate without any visible external impact. I thought of necromantic séances, but was too distracted to pay further attention. The scholars all wore their gowns like large, eminent bats. Imagine a parallel universe where this completely shapeless, unisex cape of learnedness would have become the model for all professional gear, instead of military uniforms being preserved in mens’ suits…

I had to remind myself that here, the garment still had its original meaning. At Home, we use defunct gowns as invisibility cloaks. If you put on one of the communal gowns, everyone acts like they didn’t see you. You can make yourself coffee in the kitchen without having to say “Good morning”. My host was thrilled. “You wouldn’t believe”, she said, “how long I spent carefully listening when my neighbours went to the kitchenette in the morning just to figure out a way to start the day without immediate sociability”.

Funny how in 650 years no one here has come up with a solution to such a trivial problem. But then again, maybe it isn’t trivial. Maybe there is a deeper reason in forcing those fellows who didn’t entirely choose their company to remain present to each other, to let their research be the only withdrawal open to them.

The dead fellows do not withdraw, either. Behind us on the dark candle-lit walls were blackened oil portraits and there was an adjacent room that had more modern paintings and photographs plastered all over it. Each carefully framed. The College puts up a picture for every deceased fellow, fitting with its official name “College of the souls of all the faithful departed”. Amongst all the pale men was one woman, who must have had an untimely death since women only became eligible for fellowships in 1979. The other well-represented species besides men were mallards. The wild duck is the heraldic animal of the college and thus the most popular theme for the farewell-presents fellows present to their institution. Mallard regalia in plated silver sat on all mantelpieces.

We tried to make fun of the wig-bearing scholars, peeking meekly through layers of patina. And what with this infinite succession of more modern, hollow-faced men. Most of them looked queer and lonely. (They seem not even to have managed to form something like the Apostles at Oxford.) And yet the wrinkly faces radiate authority, and they prompt their female heirs to talk about how they don’t feel like they belong. And despite this desire not to be made to feel like one didn’t belong, belonging isn’t that desirable, either. With their scholarly scrutiny, the female critical theorists were all too aware of the history of their institution, of its training colonial administrators alongside Oxford dons. “Don’t you realize”, I wanted to insist, “they are dead and you are alive?” But I was a guest and tried to behave in a way appropriate to the surroundings. For me, of course, the perspective was different: I’d been invited by a brilliant young woman philosopher, it was she who represented the college to me, not the portrait gallery behind her. Maybe they should remove some of the stuffed mallards and make space for mirrors. But even then: wouldn’t we simply doubt the reality of our images, given the misfit with all the surrounding ones?

Perhaps the real advantage of a commune over a college is that you don’t only chose your cohabitants, you also chose your genealogy. Ham Spray House, Worpswede, Fresenhagen. Or maybe we are particularly lucky and like even what we didn’t chose: retired agricultural collective workers. They wander through our garden and tell us how they, too, lived in that bloody cold manor house when they were young. Back in socialism.

Part of the monastic work-devotion is that even with such opulent dinners, the fellows go to bed so as to rise early.

High on performance-adrenalin, I made my way through the dark town to Catweazle Club. I had hoped to catch Laura’s performance, but was too late for that. I was pleasantly surprised to find the atmosphere changed from my last visit, about five years ago. The celtic-revival fashion of elaborately plated blond hair seemed to have passed. The main wall was repainted with a huge portrait of Frida Kahlo, whose facial expression was more like Angela Davis. And then, on the other side, a very good image of Nina Simone.

A young poet entered the stage (Phoebe Nicholson, as I learned from Laura later). Very athletic and butch. “… when they pare me open / on the autopsy table,”, she started reading “I will leak clear water, / salt-smelling, the sea…” I was struck. “I have seen pictures in books of /other people. / How they look inside with their muscles (…) / I have studied cysts and smokers’ lungs, / how their bodies will rust like old houses, (…) /Meanwhile, I can’t believe / I work the same.”

This person, I thought, with her calm, cheeky confidence. She is trading the magic potion we would have needed in front of the uniform pictures. Then even the mallards could stay there.